Tuesday

Escape is my aim but my nostrils root me in greater Glasgow when two friends embark at Dalmuir harbouring a sharp scent of cannabis in the folds of their clothes, unfurling as they rise or shuffle in their seats.

Sooner than expected, though, the train leaves the conurbation behind, and we are in the autumnal Highlands. The full leafy spectrum is on display, from boldest crimson to chlorophyllissimo. Although delayed by 10 minutes, we reach Oban in time to catch the ferry. I bungee-strap my bike on the car deck and survey the crossing to Craignure in the mild mid-October open air.

To be among the waves again is nourishing, although there really is minimal chop. The auburn-coloured canine is audibly perturbed and visibly agitated by the uneaten scotch egg in my backpack. I shift my position to minimise (his/her?) distress, although perhaps it is more torturous to be just beyond a lead’s breadth from a decent sniff? The dog is forbidden to eat while travelling, I’m informed. No snacks for Scooby this afternoon.

Listening to the Calmac announcements convinces me that there is at least partial truth in the factoid that the Highlanders, coming to English as a second language from the Gaelic, speak it in its purest form. My ear delights in how carefully each phoneme of the word “signal” is pronounced, alas to the detriment of any safety message being conveyed.

Tobermory is 21 miles away. I aim to make it for 5pmish. It’s a comfortable start with (surprisingly, because there is a specific announcement just before disembarking regarding single-track roads) two lanes and gentle inclines until you reach the village of Salen (pronounced “sall-en” not “sail-en” like the witch trials). From then on, after a false sense of security afforded by the flat and winding shore of the seemingly endless Sound of Mull where several fishing boats have been inexplicably but picturesquely abandoned, you are driven up and down and up and down ad nauseum till one fantastic descent before the capital where it opens up to two lanes again and you can move to the lower grips of the handlebars for the full freewheeling thrill.

Hidden by hills hitherto in its natural harbour, Tobermory reveals itself with its unmistakable rainbow facades. My first encounter with Mull, not knowing it was Mull then, was with the town’s fictional alter-ego, Balamory. In a sense then, I had been here before and coming across Tobermory for the first time in the flesh was a recognition as much as a discovery. As for Mull itself, I first became conscious of it as a distinct entity on the BBC’s Autumnwatch where they memorably covered the rut of the stags (one seen from the window of a bus on Day 3) and the frolics of the otters (only glimpsed on road signs telling me to watch not to run one over).

Yet more steepness greets me as I get into the town proper. I wheel my steed up the last summit and ring the doorbell for the B&B which is to be my abode for the next three nights. My bike lodged safely in the back garden shed, I shower then make my way down to the main street to get my bearings and sustenance in the yellow of the primary coloured buildings featured most prominently on postcards of the harbourfront.

Wednesday

I choose to take my petit-dejeuner at 8.30 so as to dine with my fellow guests. This was requested off the back of my enriching encounter in Ferns with the motorcycling Dutch couple and the American solo traveller.

Retirees were to greet me once more. This time, Australians. They were on a three-week tour of the UK and Ireland and leaving the next morning for Skye by way of the Glenfinnan aqueduct to watch the Hogwarts Express puff across the valley. Their itinerary was to cover the North Coast 500. No time for Orkney regrettably as changing flights would have cost 1200 dollars. Perhaps next time?

The husband wasn’t a fan of personal injury lawyers or criminal defence. Commercial law, though, they’ll never stop needing that. I said that was the one area I didn’t want to go anywhere near. Cue a minute or so of awkward silence.

I said how I thought Mull was quite a big island – bigger than I’d anticipated; I would need to take a bus to get the boat to Iona tomorrow. Australia’s a big island, isn’t it?

This precipitated a long monologue about the vastness of Australia and, in particular, the pleasures and pitfalls of 4×4 desert driving in the outback.

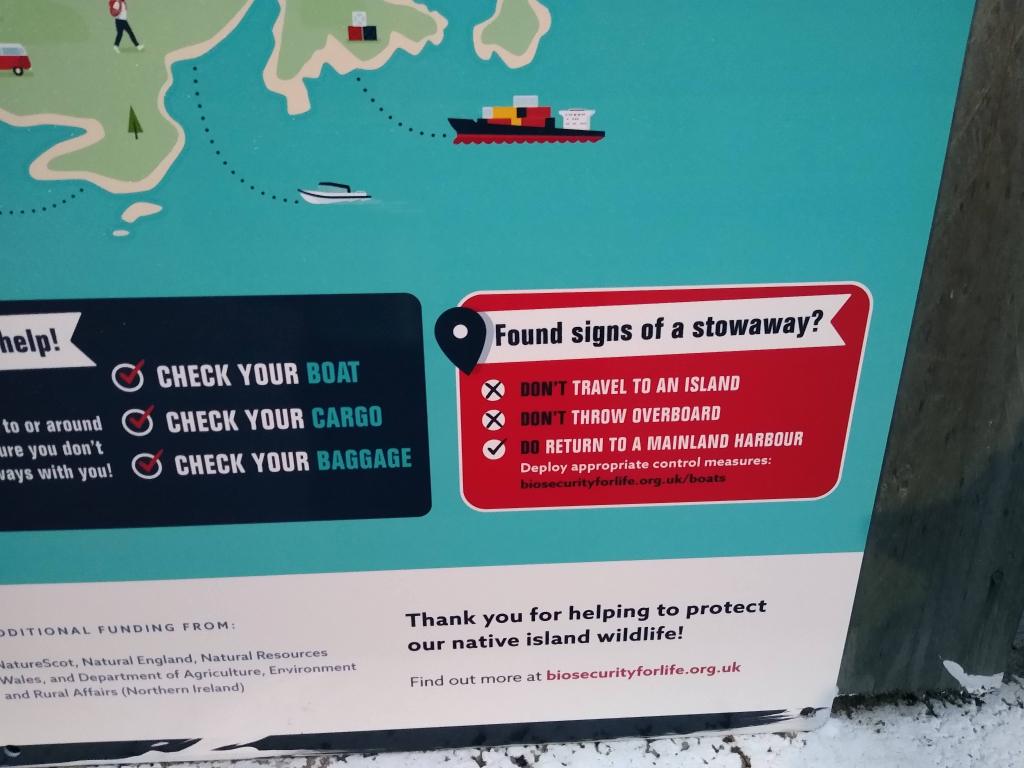

When our host returned we got to talking about native and invasive species, snakes in Scotland and Mull’s anti-stoat campaign, whereas otters are seemingly beloved.

My first destination was Calgary Beach. The city in Alberta, Canada is named after here although there the locals pronounce it with two syllables instead of three according to Wikipedia.

It was a rainy start but luckily I had my waterproof trousers. I unnecessarily locked up my bike and rounded the bay watching waves transfer their energy, advancing left to right, traversing the extremities of my peripheral vision. Rippling and writhing like the adders and slowworms of this morning’s breakfast table before crashing, fizzing away to nonexistence, withdrawing stealthily and gathering strength for yet another assault.

I am reading Virginia Woolf’s The Waves and as I walk along the shoreline I think of her and the River Ouse, weighed down by stones to facilitate sinking. The lure of the embrace of the waves; freshwater for her, but the principle remains. My mind flicks back to a character in the Clayhanger novels by Arnold Bennett who attempts the same in Brighton. To be recommended – the novel, perhaps not the suicide method.

After Calgary, I was Ulva-bound, an island off Mull’s northwest coast. The road there wound up and up in multi-phased ascents, false summit after false summit. Several times I had to dismount and walk my bike up due to this demoralising progress; often my momentum was broken up by a car I had to let pass on the narrow track. The fruits of my labour were to be won, however, when I hit Dervaig and got to downhill gradients of 14 and 20%. I did have to exercise some restraint though because as well as rapid plummets were hairpin bends and blind corners – not that there is a huge amount of traffic in north Mull, but best to avoid head-on collisions if at all possible. Both brakes, front and rear required application.

Before Ulva, I came across the Eas Fors waterfalls. I threw my bike down on the grass and scrambled up to a better vantage point. An upper tier seemed accessible if all four limbs were set to the task and so I climbed. Mull seemed to be perpetually gushing from its hillsides but this series of cascades were its most vigorous and characterful, so well worth inadequately capturing on camera.

The place where you get the ferry to Ulva is imaginatively named Ulva Ferry – a subordinate entity, like Port Glasgow, I suppose. To get across you need to pay the ferryman £10 to board a craft that seems like it could have been created on Scrapheap Challenge. In fairness, there is no other way to reach Ulva if you don’t have your own boat, and it is a return.

I took my bike across but ditched it almost instantly as there are no roads, just gravel path and trodden track – a travel tip for Ulva. Most of the time on the island I spent on foot along the woodland trail – a welcome break from 2.5 hours cycling. I did not encounter a single resident, just wandering livestock and an abandoned tractor in the middle of the forest. After having got mildly lost for a few minutes, I regained the woodland path after a worthwhile coastal detour.

Arriving at the pier, the ferryman was on the mainland side. Finally, I did meet two locals, one astride a quad bike. I remarked that she was unlikely to be boarding the HMS Scrapheap Challenge on an ATV. They were heading to Gometra whose name seemed to me to be more suited to a dying star than an island accessible via a tidal causeway off the west coast of Ulva.

Back on the mainland, I had 20 or so miles to go to complete my circuit of north Mull and regain Tobermory. After my chip shop tea, I settled down for an earlyish night before tomorrow’s 7am start involving a bus to Fionnphort and from there the ferry to Iona. My other option, due to Mull’s vastness, would be over 100 miles of cycling in a single day, which was not an appealing prospect.

Thursday

Bus 2 of 2 was driven by a chipper Edinburgh man easy to laughter and attempting to bring everyone into the joke with moderate to good success. A lady of about 60 in a silver jacket approaches. “Oh no,” he says, “She’s already complained, she might take a bit of talking down.”

The subject of her complaint was that they had recently merged the service bus and the tourist bus to the detriment of the residents. Today it was hard not to see her point as they had held the bus back to suit the visitors arriving from the delayed ferry who’d paid for Staffa and Iona tours rather than sticking to the schedule which would have allowed her to keep her appointment in Fionnphort. Annoying too for her to hear the running commentary of the driver for the benefit of the visitors when she just wanted to get from A to B. It was to our benefit though, and helped contextualise the landscape, giving colour and interest to territory seemingly untouched bar the incursion of this snaking single track.

Almost as soon as we stepped on the ferry at Fionnphort a disembodied voice announced, “We will shortly be arriving at our destination. Could all vehicle drivers please proceed to the car deck for disembarking.”

The boat is packed and no one wastes time after the first step on terra firma in marching up through the villages and following the unmissable sign – “To the Abbey and [somewhat apologetically] Nunnery”.

It is the latter of the two that one first comes across. These are true ruins, left as such, whereas the abbey itself is a working building used by the Iona religious community, reinforcing and updating the medieval fabric where necessary to keep it watertight and liveable in the modern era. The nunnery, in comparison, though is relatively new and was founded in around 1200. With its remote location, it has been well preserved, although no nuns have been here since the reformation. You can still sit on the cold stone benches of the chapterhouse and contemplate the austere life of those daughters of the aristocracy sent here in pursuit of prestige and the favour of God.

At the Historic Environment Scotland ticket office, I revealed myself to be a former member of staff and managed to negotiate a concession entry fee. In a similar manner to Skara Brae on the path leading up to the abbey you are encouraged to acknowledge the significance of the journey you are about to make as you put yourself in the shoes of countless pilgrims of yore coming to venerate the seat of St Columba, missionary in the kingdom of Dal Riata, converting the northern Picts and bringing Christianity to Scotland before it knew to call itself by that name.

A little in front of the abbey stands a small hill which the audio guide invites you to climb. Here once stood Columba’s writing hut where he penned hymns and correspondence from the spiritual centre of the British Isles.

On the approach to the abbey, you are struck by the presence of two great stone crosses with elaborately carved biblical scenes and Celtic knot designs. In addition to the simple crucifix is the interposed ring creating four gaps between the beams. From these were hung wreaths and other adornments on liturgical feast days. The furthest from the abbey is the more striking, standing in isolation on the same spot it did during the middle of the 8th century when it was erected. It is dedicated to St Martin of Tours. The other cross, which stands in the shelter of the abbey courtyard is a modern reconstruction of St John’s Cross – the original is on display in pieces in the museum. It is astonishing to think that before Iona there is no record of crosses with interposed rings. The Celtic crucifix was yet to take its place in Christian iconography. This is where it all began.

Should you visit Mull and if so, how?

In sum, I would thoroughly recommend a couple of days trip to Mull for anyone in proximity to the West of Scotland. If you are comfortable with or at least undaunted by a lot of hills then take a bike, otherwise, a car is necessary to see all the sights, although you can get away with the ferry and bus if Iona/Staffa is the extent of your ambition. As the tourist campaign literature says, “a day is not enough” but two days is probably just about sufficient!