In 2025 I qualified as a solicitor. Practically, this has little substantive effect other than 1) being able to call myself a solicitor and 2) being able to be sued in my own name for professional negligence and complained against via the SLCC.

I was pleased to be retained by the firm I trained with and have remained in their employ since qualifying in September.

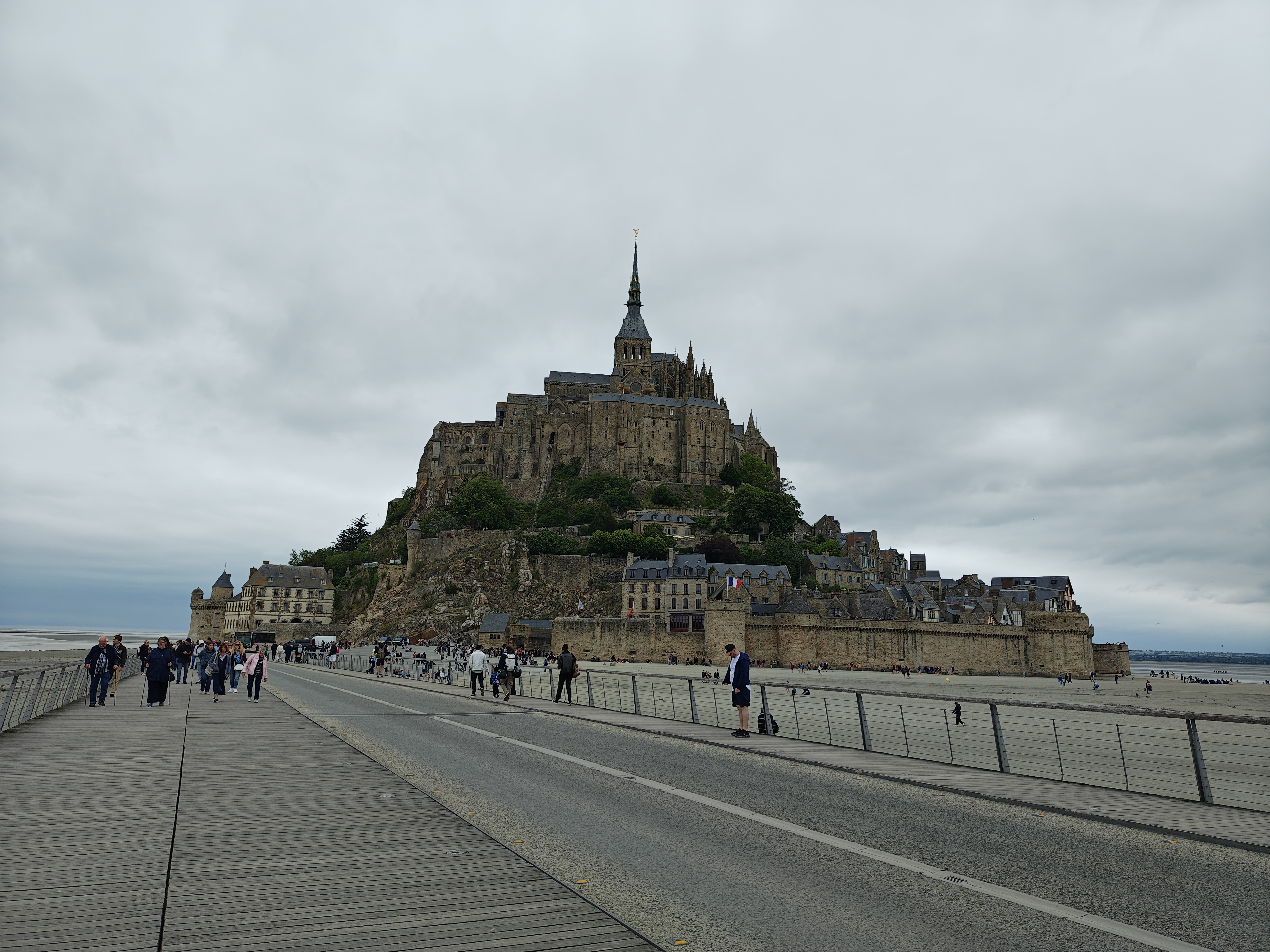

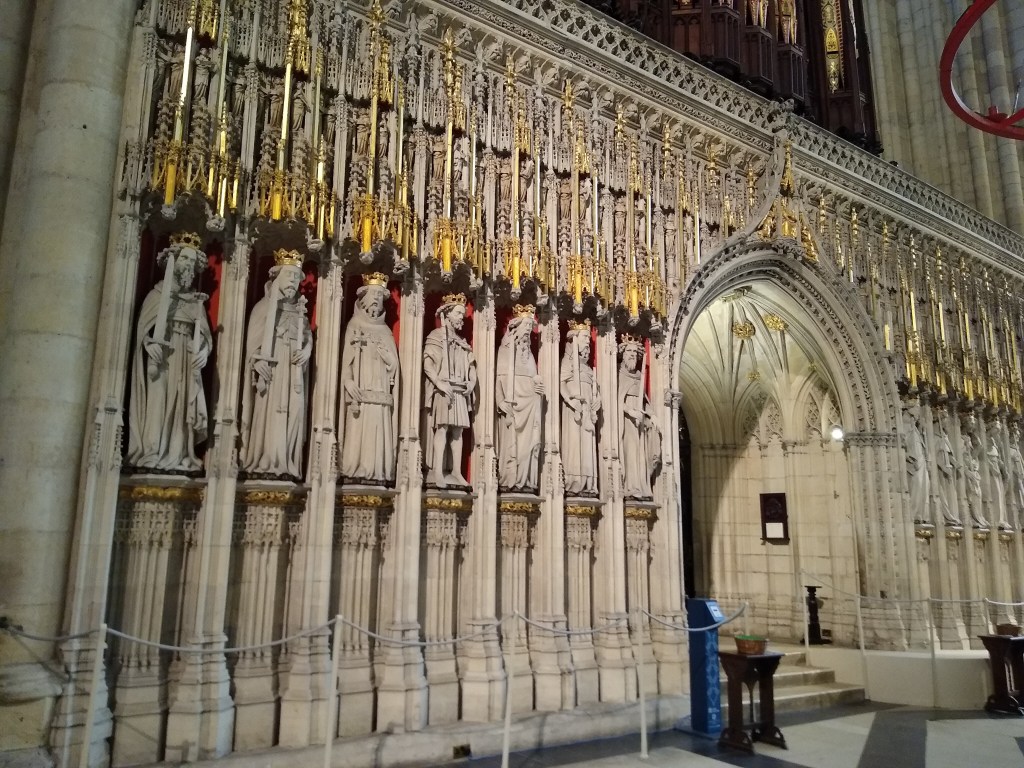

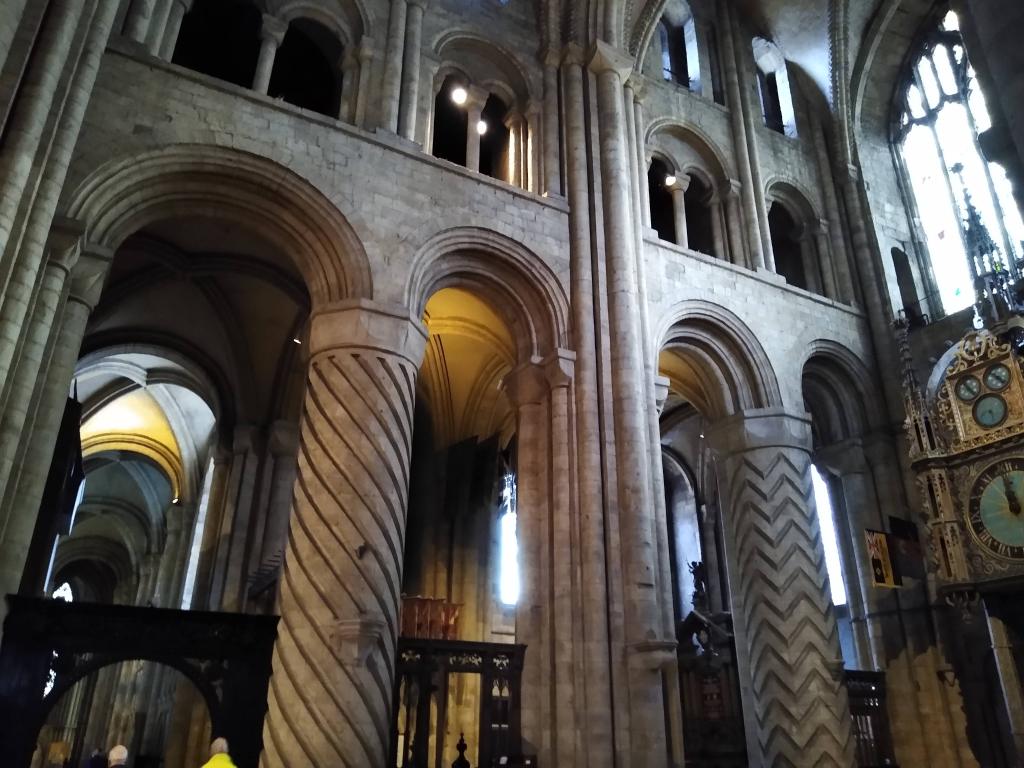

In terms of international travel, I left the UK but remained firmly British while visiting Jersey. I then got the ferry from there to St Malo, half-and-halving it for a week in the Channel Islands and Normandy.

Internally, I took my longest ever train journey from Glasgow to Cornwall in June for H—‘s sister’s wedding in June, and in November we took the ferry from Kennacraig to Islay.

Gig highlights included Japanese Breakfast, Geordie Greep and Maruja.

My best gig of the year was English Teacher at Barrowlands. This was on a Wednesday, and Monday saw me stricken with perhaps my worst cold of the year. I had warned H— I might not make it, but I lemsipped up and got on my bike.

Their 2024 debut, This Could Be Texas was a late discovery for me at the start of the year. It combines verbose half-sensical lyrics with intricate instrumentals, often adding stings and horns/woodwinds to the standard bass/guitar/drums setup. They build on a musical posture pioneered by Black Country New Road, except punchier and punkier (in my opinion). In some modes, though, they emulate The Smiths as on ‘I’m Not Crying You’re Crying’. My favourite, though, is ‘Nearly Daffodils’ with other highlights being ‘R&B’ and ‘The World’s Biggest Paving Slab’.

Another autumnal gig with a harrowing backstory was Haim at the Hydro in October. I had put off going until the night itself because everyone had Halloween plans and I felt I couldn’t justify the ticket price just going myself. Yet at the last minute, I checked Ticketmaster resale and got one at £20 less than face value.

Again, I decided to cycle. In order to get to Finnieston, I go along Lynedoch Street and turn right onto Lynedoch Terrace. Unfortunately, on the night in question, there was a rather large pothole close to the centre line, which I entered and which caused me to dismount unexpectedly.

A graze to the right knee and shin, and some moderately cramped up hands, which I put out to try and break my fall, were the toll of the physiological damage. My bike’s handlebars were bent out of shape, but could relatively easily be remoulded to their original configuration. A passer-by helpfully shouted, “You’ve got to watch out for potholes!” as he looked on. The offending hazard has since been filled in.

I regathered myself and continued on my journey. At the Hydro a loading bar informed us of the progress to stage time. A rolling text LED bar above the stage (i quit themed) was deployed at various intervals through the show. Occasionally self-indulgent, it was fun overall.

My real challenge was to come post-gig. When half-way home, the chain decided to fully misalign, obviously having been knocked off centre during the pothole incident. This was not only such that the bike was incapable of being pedalled any distance, but that wheeling it by hand caused a horrible grinding and clicking noise for the duration of the highly conspicuous 25-minute walk home.

Happily, my bike was restored to some of its former glory the following Sunday when a few turns of the Allan key brought the chain into temporary alignment, and it was retuned the following week with the proviso that in bending back the part, there was a risk it would snap (it did not).

I have continued to enjoy Magdelena Bay in 2025, who have been releasing singles throughout the past couple of months and at this rate should be putting out a new album in 2026. Another late to the party pick would be the Australian act GUM who released Ill Times in 2024, alongside King Gizzard and the Lizard Wizard’s Ambrose Kenny-Smith.

Mac DeMarco treated us to an album this year, simply titled Guitar. A few fewer tracks this time around compared with the post-Covid One Wayne G comprising 199 songs. While last year ‘Holy Holy’ was my song of the year, in 2025 ‘Holy’ comes close to claiming the crown. Geese too had a new one, a lot looser and more through-composed compared to 3D Country but enjoyable and rewarding on repeated listens.

The only album I bought on vinyl this year was Preoccupations’ Ill At Ease, ‘Focus’ being a particular highlight. Spotify, however, claims my top album was Clarity of Cal by Vulfpeck (undoubtedly accurate in terms of plays on that platform. I also unashamedly enjoyed Lady Gaga’s latest, MAYHEM, following unexpectedly attending a launch party in Polo with friends. Additionally, in that kind of vein, I was a fan of PinkPantheress’s new record this year.

2025’s biggest music news for me was King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard removing their catalogue from Spotify. They have done so in response to the CEO investing in military tech companies including drones and AI for warfare. According to an interview in NME, Stu Mackenzie explains the decision to come off Spotify more as a “straw that broke the camel’s back” situation, citing the funding mechanism for musicians as a factor militating in favour of the move.

In personal music news, 2025 was the year my mp3 gave up holding its charge, and I got a new phone that can only work with Bluetooth headphones. Yes, I have joined the airpod masses. In fact, they are drolly called ‘NothingEar’ with bright yellow buds and transparent stems.

This has meant that my streaming consumption has increased, and I’ve been downloading far less. Before I did partially justify my continuing to purchase from iTunes on an ethical basis. Another factor was the utility of having a separate place with all my music without having to rely on wifi and without the distraction of a phone that can do everything and which notifies you every 10 minutes.

I discovered the existence, now, of such things called Dedicated Audio Players. Apparently, there is a market for the kind of experience I had carved out for myself. Except now phones are just as good as most MP3s in quality and can store just as much. The only selling point is truly lossless audio or pre-amps within the device. This pushes the price of something truly better than a phone to approaching a grand.

Of course, another option would be to mod an iPod Classic, which a few people do successfully. Apparently, this has superior quality to most phones and streaming, but it does seem like quite a few extra steps.

So, in 2026 I will look for a way to listen to music that is somewhat more ethical and compatible with enjoying the art form of the album in the way it was intended to be heard.

Other cultural highlights include, in film, The Phoenician Scheme directed by Wes Anderson and Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another – an Anderson double victory for this medium, and featuring two very winning performances by Benicio del Toro. The other del Toro film released this year, I have already reviewed extensively.

While it would be uncontroversial to say that Frankenstein is Mary Shelley’s magnum opus, this year I read another of her novels The Last Man, which is set in the then far future – the 21st century. Unfortunately, I was rather disappointed about the lack of imagination in terms of future technology and societal relations (they still travel on horseback, and lords continue to have real political power). It was probably the classics book group’s worst read of 2025.

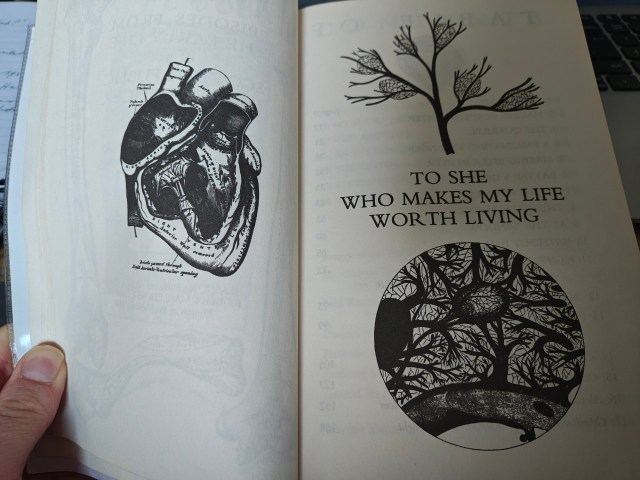

That being said, it was good to get the opportunity to re-read Poor Things and Anna Karenina. My personal highlight was probably Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley, which I experienced as a kind of Walter White narrative (obviously not what she had in mind in the 1950s but death of the author and all that). I am also geared up for an informed criticism of the upcoming Wuthering Heights adaptation.

In contemporary fiction, which I did have some time for, I had my first experience with Sally Rooney in Intermezzo; I must conclude that the hype should probably be believed. I also read Butter by Asako Yuzuki, which is an intriguing insight into Japanese society and its expectations of women, as well as being memorable for its vivid descriptions of cuisine with which its protagonist becomes obsessed. This sparked a bit of a culinary journey for me, and I started following Andy Cooks and Joshua Weissman on YouTube – many a fine dinner was had on the back of their tutelage!

Let me end this epistle by wishing you all the very best for 2026. See you in the New Year!