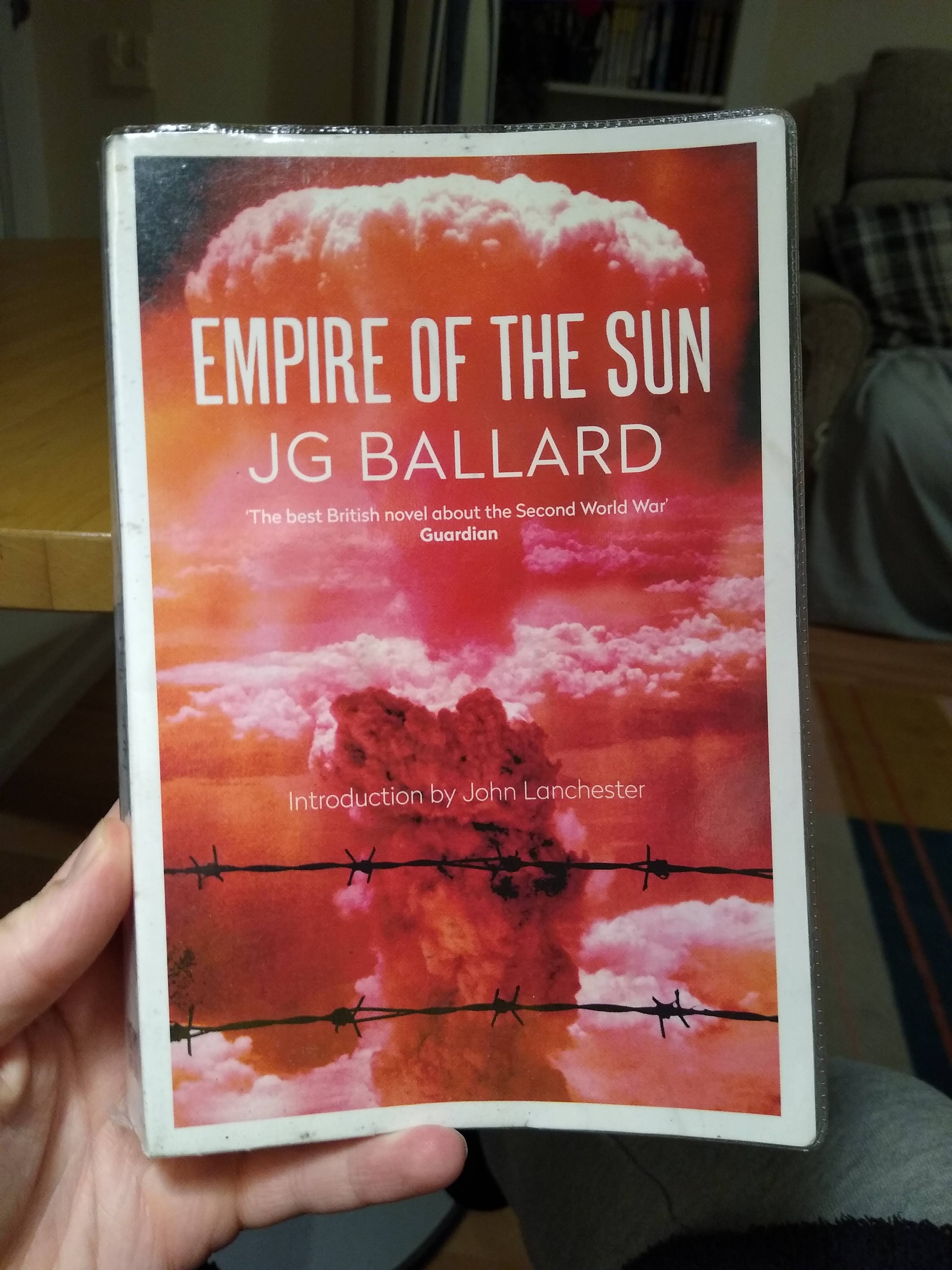

I first read J G Ballard when I was getting into the idea of the postmodern. His novel Crash is seen as a seminal (pun intended) text.

Crash is a difficult book, conceptually and also because it is rather disgusting. The J G Ballard interested in bodily fluids and excrement is still present in his war novel Empire of the Sun, as is the sexiness of modern machines, in a disquietingly literal manner. Whereas it is automobiles fuelling the autoerotic in Crash, aeroplanes awaken latent desire in the adolescent protagonist of Empire.

The novel is challenging but less for its postmodernity than its uncompromising depiction of a Japanese prisoner of war camp on the outskirts of occupied Shanghai. For me, the setting of Shanghai was fascinating as an international hub where all the actors involved in the Second World War were present in some way. The International Settlement was a British- and American-dominated portion of the city that held effective political control there; sovereignty was de jure retained by the Chinese and they, in theory, exercised delegated power. There was also the French concession, which by the 40s was held by Vichy France. In the 1930s Shanghai was the only place to accept unconditionally Jews fleeing persecution in Germany.

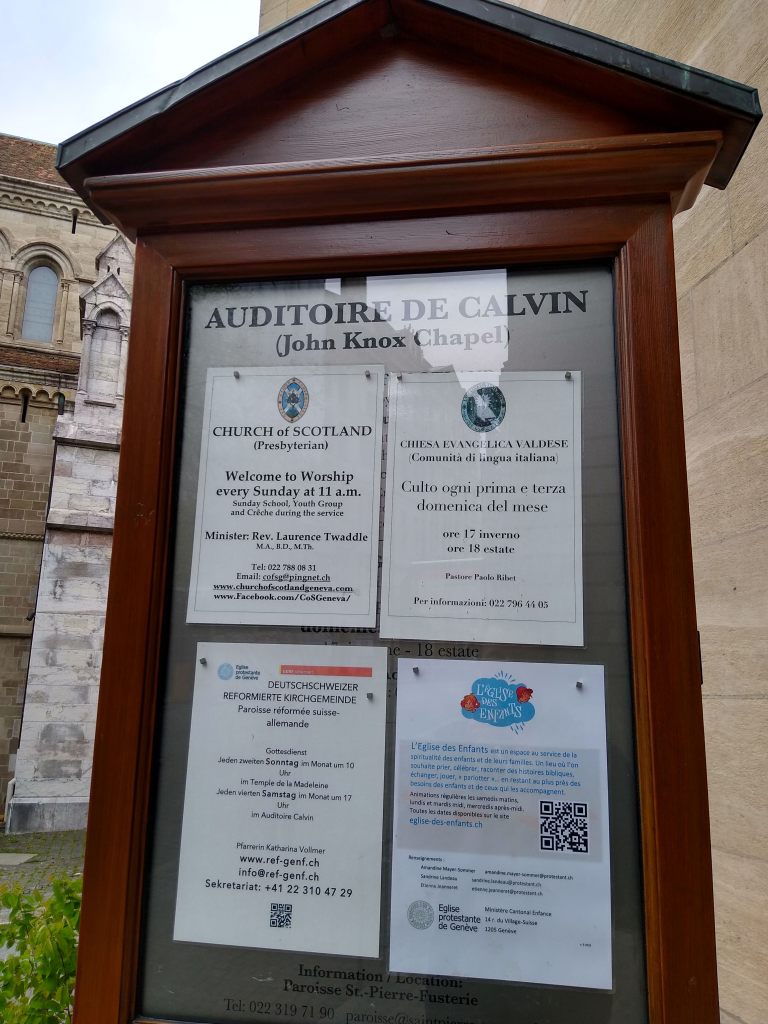

An interesting aspect of Empire is the protagonist’s relationship with Britishness. Jim has never set foot in Britain, having been born and brought up in Shanghai. He has led a rather separate existence and socialises pretty much exclusively with fellow expats. This is in line with the author’s own childhood experience. It is a protected and protective bubble sheltering him from the seriousness of international developments. This makes the contrast of the world unleashed by the post-Pearl Harbour attack all the more shocking.

Jim contemplates the horror and brutality of the mid-20th century with an unflinching gaze filtered only through his naivety and trusting nature. He has “confused” ideas, the most striking of which is his fascination for the Japanese which easily coexists with his admiration for the Americans and, as previously mentioned, his obsession with aerial warfare.

There is a three-year time jump in the action, which is a great relief to the reader after 100 or so pages spent in late 1941 and early 42. Despite Jim’s optimism, these are very grim years both on a local level, as he looks forward to the opportunities to be had on transfer from a detention centre to an internment camp, and from a global perspective where the Axis look very much to have the upper hand. The time jump propels us to 1945 by which time the Japanese are losing. It is a very compelling stage in the conflict as they do not let up the brutality but instead increase it in response to the collapse of their imperium. Counterintuitively, the war coming to an end makes things much worse for the prisoners as rations are cut and the security of the camp becomes far less reliable, with frequent American bombing raids.

When the war finally does end Jim’s woes are far from over. The power vacuum instantly turns allies into enemies and new conflicts break out between nationalists and communists, the bombing of Nagasaki and Hiroshima having finally forced the Japanese surrender. For Jim, there is no gap between the end of World War II and what he perceives as the start of World War III.

A lesser consequence of the war in global terms but of significance to Jim is the shift in British identity that has taken place while he has been effectively cut off from the world news cycle. In 1945 he is re-united with an American he meets in the post-Pearl Harbour attack who gives him copies of Life magazine in a pathetically one-sided exchange for Jim’s labour. In these pages he reads of the “nation” that “stood alone” – the Battle of Britain has already been mythologised as a re-imagined community. The sun has set on the Empire as it rose (and fell) in the East.

Jim’s main feeling towards his fellow “Britishers” is contempt. He finds them unnecessarily complicated and inclined towards complaining. He is equally contemptuous of the Chinese and their perceived passivity in the face of imperial domination. Jim admires the Japanese for their discipline and activism. He looks up to the Americans for their optimism and abundance.

I am going through a bit of a Japan phase at the moment. It is not the usual one of anime, sushi or martial arts. I am interested in the wartime Japan of the 30s and 40s as it seems so remote from the country we would recognise today. Perhaps it is just my Western perspective but I don’t feel that the Empire of that time is nearly as interrogated as Nazi Germany even where in many cases its war crimes were no less.

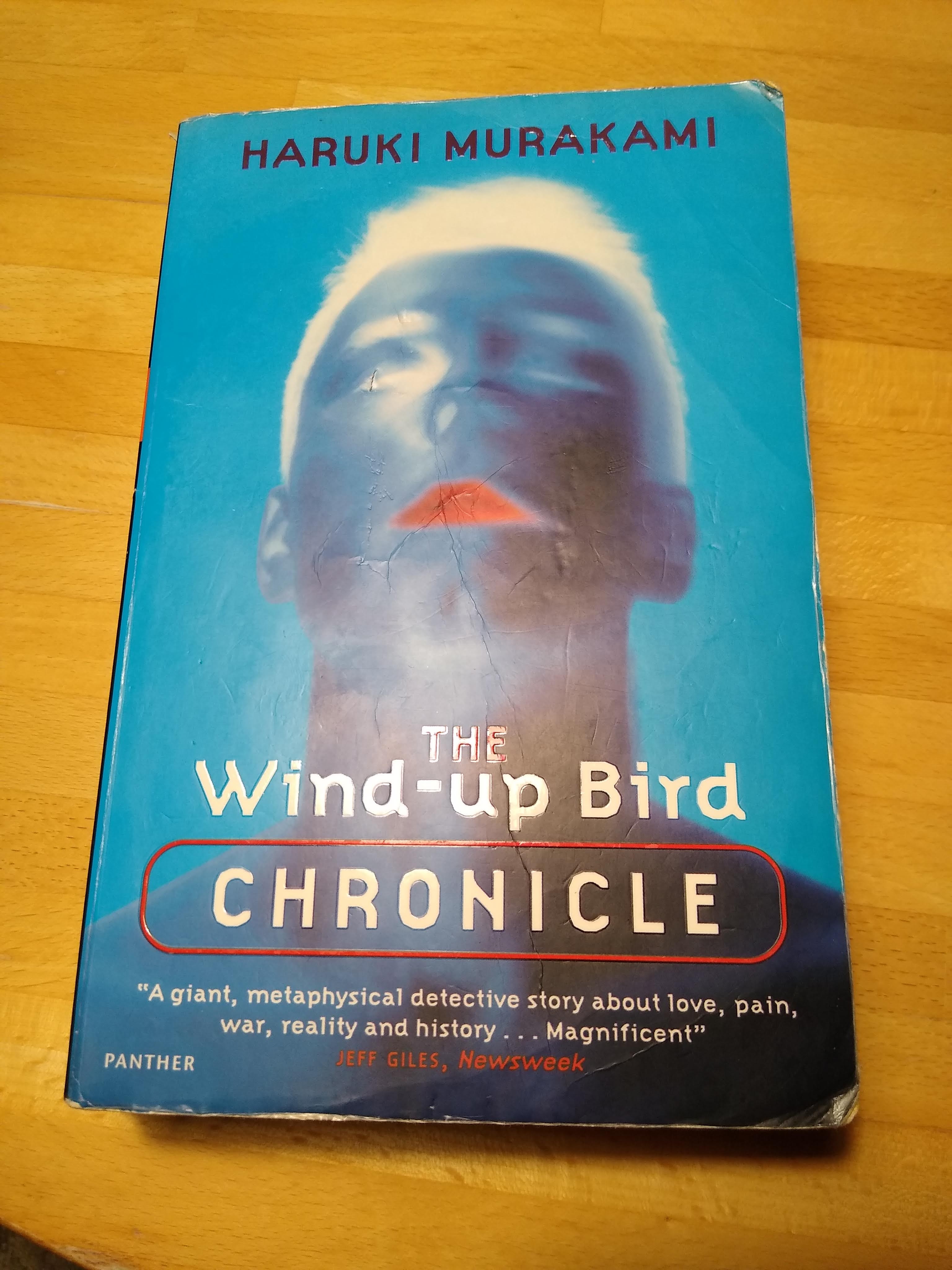

Alongside reading Murakami’s depiction of Japanese Manchuria in Wind Up Bird Chronicle I went to watch a screening of the 1980s film Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence starring David Bowie this summer at the Glasgow Film Theatre. I highly recommend the film, set in Japanese-occupied Indonesia and featuring an incredible synthesiser soundtrack by Ryuichi Sakamoto.

A line that sticks out to me from that is, “We are not Germans! There is no Geneva Convention here.” I’m not sure the Nazis were renowned adherents to international law, but it is an interesting insight into the moral mindset of those running Japanese prison camps in their occupied territories.