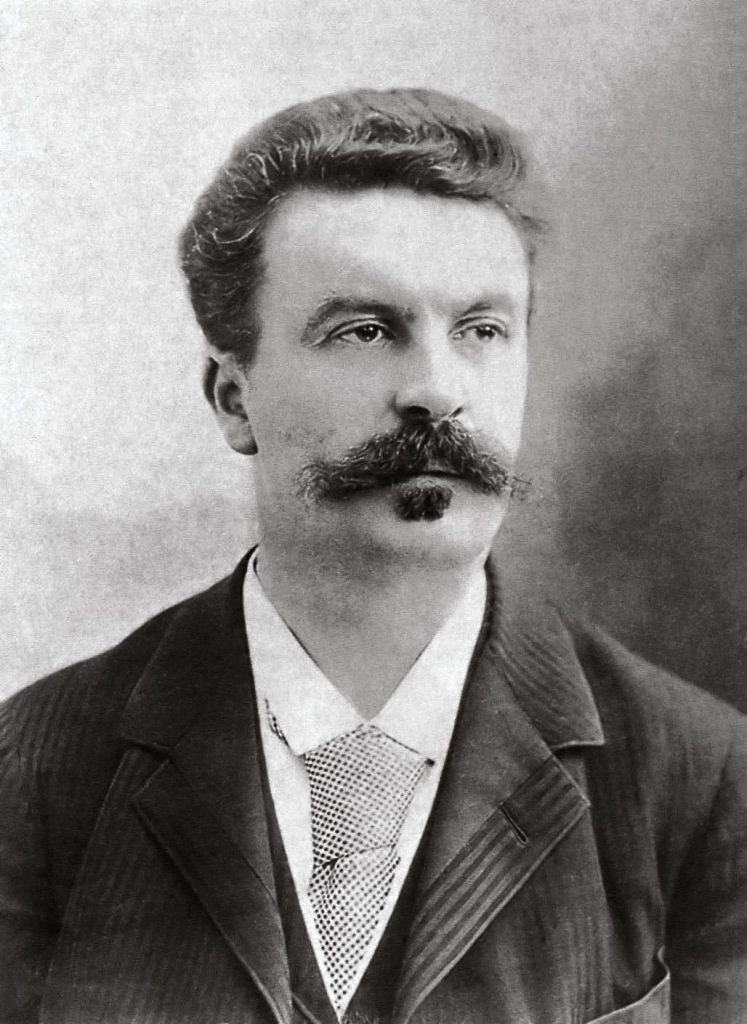

I was a couple of paragraphs into Guy de Maupassant’s short story Corsica when I had a sudden and vivid sense of déjà vu. Where had I read this before? Was it in an educational context? Perhaps at school? But why would I be reading it there? Surely there were enough short stories in the original English not to have to resort to literature in translation. My language at school was German, so it can’t have been there.

Some days later the recollection appeared to me so suddenly I could almost feel the synchronous firing of synapses, the vaguely familiar shocked into startling clarity.

In the summer of 2022 I had decided to get semi-serious about learning French and found a tutor based in Glasgow online. We discussed my learning goals – to read the great writers in the original being among them – and she set me de Maupassant’s contes to work through week by week, though my level was such that each story was a line-by-line puzzle to unlock. By the end of that summer I did have enough comprehension to leave me with distinct images and outlines of plots, even if the nuances of the language in all likelihood flew over my head. This particular Corisican conte was absorbed while awaiting a Flixbus in Aachen, Germany (or should I say Aix-de-Chapelle?) in mid-October. It was to take me from there back to Amsterdam after a quasi-pilgrimage to the octagonal basilica of Charlemagne/Karl der Große.

A combination of the commitments of the law diploma, the inherent awkwardness of such an arrangement and a lack of persistence/willpower sufficient to overcome these meant that the French lessons fell by the wayside. I have continued in self-study with varying degrees of diligence over the subsequent two years but never with the intensity of purpose required to break into something approaching fluency.

Nevertheless, my cultural interest in France and the French has not waned. This year in particular has offered me the opportunity to read the French greats of literature (albeit in translation) with Zola’s Germinal being the book group pick for June and October’s being de Maupassant’s collection of A Parisian Affair and Other Stories.

Although contemporaries, Zola takes a backward glance at the then-expired Second Empire, whereas de Maupassant is more of an observer of its collapse, Prussian/German ascendance and the Third Republic that succeeded it. Several of his stories take place during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/71 or are influenced by the trauma of invasion, occupation and the obvious shame of no longer being the top dog on the European continent after centuries of supremacy. One such story that skirts around the edges of the war takes place in de Maupassant’s native Normandy. The train in which the narrator is travelling breaks down outside a small town and the passengers are asked to disembark for several hours to allow it to be fixed. Considering how he will occupy the time, the protagonist remembers an old university friend whom he remembers now lives in the town, practising medicine. Looking him up, helpfully directed by the first local he meets, he stands before his pal and several thoughts occur to him – he’s let himself go, he positively radiates “provincial”, he’s barely recognisable but it’s all too obvious what’s happened here – his mental universe has shrunk to the size of small-town life:

Dans un seul élan de ma pensée, plus rapide que man geste pour lui tendre la main, je connus son existence, sa manière d’être, son genre d’esprit et ses théories sur le monde.

In a single moment of thought, more rapid than a handshake, I knew his existence, his mentality and his theories on the world.

Isn’t it boring to live your life in this little town? he asks him.

Taken together, a little town is like a big one, the provincial replies. The happenings and the pleasures are less varied, but when they do occur, they are of greater significance. One’s neighbours are fewer, but one encounters them more often. When you know all the windows in a small town and know every person behind them, you have much more interest than you would in an entire Parisian street.

The narrator accuses his old friend of parochialism as he relates a proud history of the town from Julius Caesar to the present. He replies, “Parochialism, my friend, is nothing other than a natural patriotism.”

Turning to the subject of the recent humiliations at the hands of the Germans, the provincial refuses to be caught up in the Germanophobia:

Je suis Normand, un vrai Normand […] je ne le déteste pas, je ne le hais pas d’instinct comme je hais l’Anglais, l’ennemi véritable, l’ennemi héréditaire, l’ennemi naturel du Normand.

I am a Norman, a true Norman […] I do not hate [the German], I do not have the instinctual hatred like I do for the Englishman, the veritable enemy, the hereditary enemy, the natural enemy of the Norman.[1]

This exchange is really only the frame of the main story, which is Madame Husson’s Rose King (adapted by Benjamin Britten in his opera Albert Herring playing in Glasgow currently) but to me, it is the more captivating one. The pretext for the tale is the provincial explaining a local idiom to his friend from the train. At the end of the story, he relates the history of his town from the Romans through Normans, to English invasions and back to French monarchs in effect showing that casting an intense gaze on the local can often reveal a Weltgeschichte in miniature. His love for the local is its interconnectedness with the universal. His head, as his fellow graduate assumes, is not buried in his sand, rather, his feet are buried in the soil, his gaze directed out across the world.

De Maupassant’s stories, in general, as indicated by the title of the collection highlighting A Parisian Affair are about the French capital as a centre of wealth, luxury, extravagance, intellectual sophistication, social liberalism and cultural refinement. That particular tale brings sharply into focus his concern with the idea of Paris and the desire of its female protagonist to escape the boredom and restriction of provincial life.

The metropole and the province are in constant tension with de Maupassant never really coming out in favour of one over the other. However, in Parisian Affair the protagonist swiftly becomes disillusioned with the grandeur of the supposed high life of the cultural elite and decides she is content to return to country life all along, having now tasted of the ideal which has been so much more attractive when remaining so – a fantasy assembled from newspaper cuttings of gossip columns, scandalous reportage and literary reviews.

These contes continue to resonate even in the 21st century, not least because of their surprisingly progressive subject matter – there is a story about openly lesbian lovers who seem to be freely accepted within the Seine boating scene of the 1880s, but also because Paris retains a hold on our collective imagination like few other cities in the world. If we have not been to Paris physically, we’ve been there imaginatively, and psychologically. Even if it’s not Paris, almost everyone will have felt the draw of the cosmopolitan epicentre; the desire to be where it is happening, at the edge of the cutting edge, the vanguard of the new.

While Paris may no longer be the world centre of cultural production, and much of its allure now is as a romanticised, digestible monument to its 19th /early 20th-century gloire, it is still a Weltstadt equivalent in stature to Berlin, New York, London and, in the last half-century, Los Angeles. Like great whirlpools they suck in the aspirational from far and wide, drowning many but propelling those perpetually who dare to swim amid the vortex.

One such contemporary swimmer/sinker is Amy Liptrot, co-director and author of the book and film The Outrun recently released in the UK this month. The metropole – London; the province – Orkney, more specifically Papay/Papa Westray – an island off an island off an island.

The story is of the author’s alter ego, Rona’s 30th year. She has returned to the islands of her childhood after drinking too deeply of London’s infinite variety of events and pleasures and immediately following a 90-day rehabilitation programme for alcoholism.

This is not a simple tale of island as antidote to city, however. Rona is initially suffocated by everyone knowing everyone’s business at the lowest point in her life. Compared with the anonymity of London life, the accountability – having to tell a version of her story to everyone she meets – is painful and only enhances her apartness. Despite growing in up in Orkney, her English parents and milder accent due to having been living South for a decade-plus continue to mark her out as other and really only provisionally/technically Orcadian.

There are only two ways to go: ferry to the mainland and onwards to the comforting toxicity of the capital or deeper tactical retreat aboard the world’s shortest scheduled flight to Papa Westray.

Here the folk are even fewer, but, it seems from their depiction in the film, more genuinely concerned about her well-being and motivation than looking for gossip. The events are much less frequent and participation is compulsory when your absence would undoubtedly be remarked upon. At first, this is burdensome, especially because in Britain socialising and drinking are virtually synonymous but by the film’s conclusion the island is having an arts festival with bonfires, costumes and chanting. People from all over have travelled to Papay to create and experience this strange slice of the particular that in its nebulous way seems to stand for the proto-ritual common to all humanity. It is the turning point in Rona’s story or can be seen as such. The sea swimming which, as I recall, had greater prominence in the book, is weirdly more akin to the thrill-seeking sensuality of addiction to be the adaptation’s lasting insight.

To declare an interest, I am from Orkney myself and so my view is not necessarily the most objective. As an Orcadian, the film was a joy to watch. Despite my drawing attention to the challenges of “provincial”, particularly island, life, The Outrun clearly comes from a place of largely uncomplicated affection for the isles and as with being in love with a person one is likely to overlook and minimise their flaws. An example of this is probably in the directors’ decision to involve the local community so much in the film. While it is, for me, astonishingly uncanny to hear an Orcadian accent featured so prominently in a major cinema release, there were definitely times when the use of amateur and, frankly, non-actors took away from the immersion.

That said, in my biased opinion, you are unlikely to see a film quite so particular with such a unique authorial voice this year. (Dune: Part Two is probably still my favourite though!)

[1] Translations are my own – was a fun exercise, and they are almost certainly flawed!

Pingback: An update: professional and personal | Flett-cetera