York

York historically claimed authority over Glasgow as an archbishopric, but the Pope dissented, naming the city a special daughter of the Church. No intercessor needed between us and Rome.

It began on a frosty Thursday morning. On the train over every branch and blade was crystalised. The most mundane undulation transmogrified. Half an hour behind schedule we pulled into the city of the white rose.

The first recognisable establishment from the station was Pizza Express, a favourite haunt of the Duke’s, though that perhaps pertains only to the Woking branch.

Number 1 on the agenda was the Minster. It’s £18 a ticket, which is a lot but your entry lasts you a year. There are free guided tours on offer but I decided to explore at my own pace. I take it clockwise from the west doors, heading initially to the transept, which contains a carved stone screen separating the nave from the choir. It has all the kings of England on it from William the Conqueror to Henry VI. I note the Shakespearean series from Richard II and scowl disapprovingly at the Edwards.

At the south end of the transept is the staggering (red) Rose Window, which survived a fire in the 80s, and before the choir is the octagonal chapterhouse.

The chapterhouse’s arresting geometry is reminiscent of the Basilica at Aachen. The sheer verticality and immensity of the space is astonishing. As one’s gaze is directed up and up you are rewarded at the full flexion of the neck with a view of the interwoven complexity of the central capstone, which is the focal point of each of the eight towering windows on every side. Every sill is fringed with dozens of carved gargoyles, each given a distinct personality with chisel and hammer seven centuries or so ago.

Mid-choir is the entrance to the crypt and the tomb of St William, patron of York. On the far wall, a mosaic proclaims, “Blessed are the peacemakers.”

Turning the southeastern corner, you come across the Cuthbert exhibition. The Cuthbert window is undergoing restoration currently, so in its place is the story of his life with accompanying illustrations in glass. A particularly amusing panel shows Cuthbert and a companion doing handstands. While the companion’s smock has fallen down to expose the undergarments, Cuthbert’s defies gravity to preserve his saintly dignity.

The museum in the undercroft tells of the city’s Roman past as an impregnable fortification. The present Minster is built on top of the remains of the fort, and there is evidence of reuse and upgrade in the visible architectural stages from Anglo-Saxon to Norman to English Gothic. Normans built with hollow columns filled with rubble whereas the later medieval Gothic style had solid columns that allowed visions to soar ever higher.

Outside the Minster, past the mason’s yard is a statue of the Roman Emperor, Constantine. He was proclaimed in York. As the first Emperor to convert to Christianity he made the slave religion the creed of the masters of the world.

By the time I had exited the cathedral, it was beginning to dim. Most sections of York’s walls were shut, but I did have time to explore the ruins of a medieval hospital in the grounds of a library before the light entirely faded.

Next on the agenda was the Shambles. To get there I had to walk through a Christmas market in full swing. Like Pilgrim, I was unmoved by the temptations of vanity fair. However, the Shambles’ quaintness did induce me to capitulate and I ended up getting a takeaway mulled wine from the mini pub on the street that supposedly inspired Diagon Alley.

At my accommodation for the night, they asked me if I was there for the snooker UK championship. Alas, no but I did watch another Trump victory before heading out for a solo pizzeria trip that brought my evening to a close. Not before Google Maps sent me along the aptly squelchy banks of the River Ouse to get there though.

Durham

Durham is built on what they call the “peninsula”. This is a strip of land almost completely enclosed by a hairpin bend of the River Wear. To reach this island from the train stations, you need to descend into the valley. What strikes you when you do are the weirs of the Wear. These are manmade steps assisting the river’s incremental descent and which salmon leap up in the autumn to spawn.

Crossing the Silver Street bridge you get your first full view of Durham Castle and Cathedral rising magnificently atop the crest of the valley and partially obscured by thick tree cover below. Nearly a thousand years of history have not detracted from the impression they leave on a mere mortal standing on the lowly cobbles beneath.

A fairly steep climb and you are at the top of Durham’s main market square. At first, you are confronted with the rear end of an equestrian statue – the image of Charles William Vane Stewart, an aristocrat of the first half of the 19th century who led a regiment of hussars against Napoleon and vigorously opposed trade unionism. The other statue in the square is, oddly enough, of Neptune – a monument to the abortive attempt to make Durham a seaport by re-engineering the Wear for the export of coal.

Onwards and upwards, though, to the summit of the hill and the main purpose of my visit – Durham Cathedral. This is truly a fortress of God. The power projection is self-evident. A building that compels a state of awe. A place of sanctuary for the outcast but also of dread for the unfortunate Covenanter POWs defeated at the Battle of Dunbar in 1650 by Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army.

The great oak doors have at their centre a copper lion’s head. In its jaws is a ring with a handle for knocking on the timber, begging entry. If your calls for “sanctuary” are answered, so it is said, you had 37 days to make it to the nearest port and into permanent exile. Ecclesiastical jurisdiction provided a window of amnesty from the laws of the land.

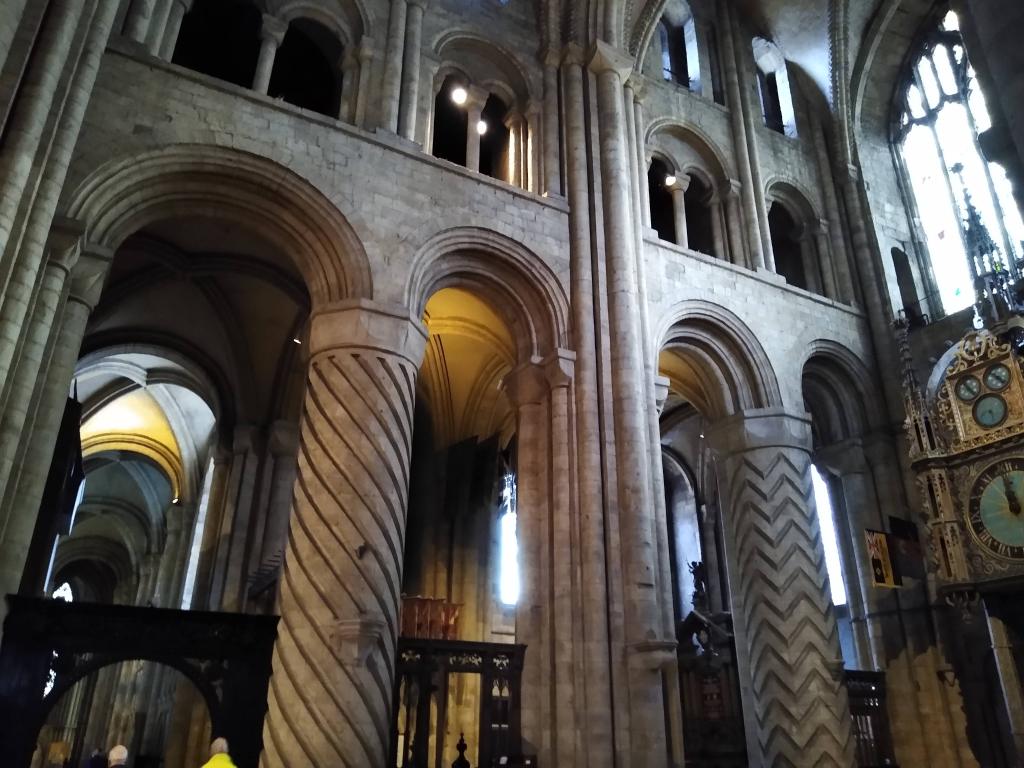

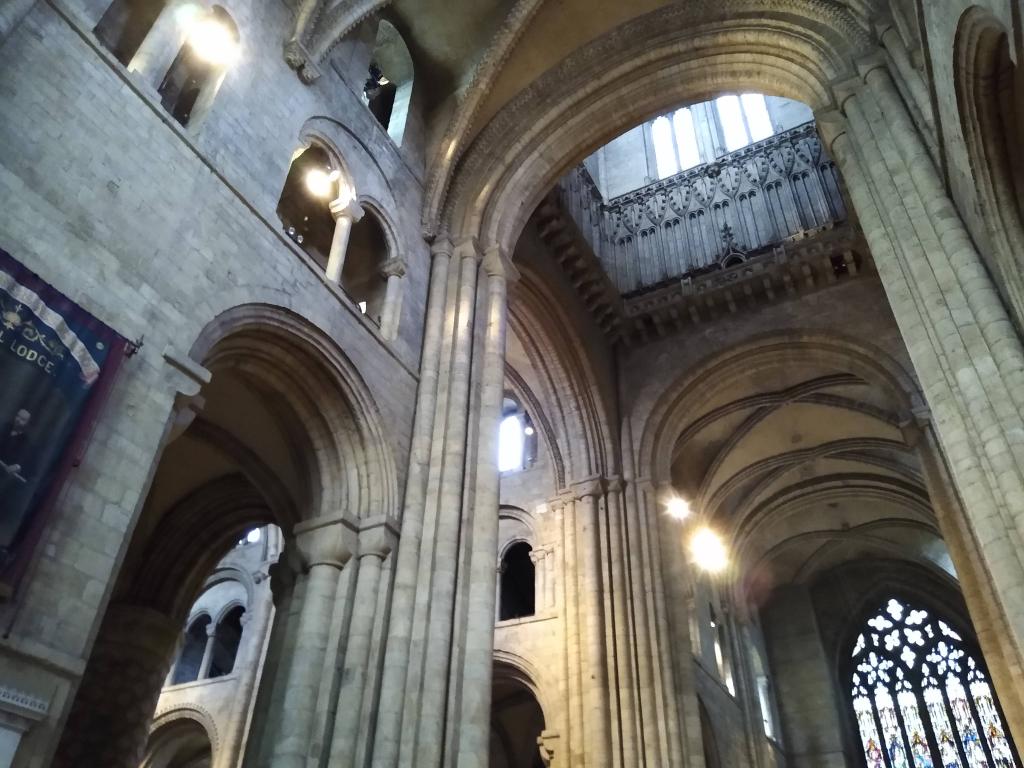

A glass vestibule greets you, and in my case also a volunteer guide who informs me that entry is free although a donation is encouraged. Through the doors and staring down the nave there is a sense of vastness but also slightly discomfiting familiarity. The visionary masons who created this temple were the same as those who helped build up the great stone minster at Kirkwall to house the translated bones of St Magnus. Although the scale belongs almost to another order of magnitude, the similarities can be seen in the thick, round columns and Romanesque arches. Not squat exactly, but solid. Substance as well as ethereality. These two cathedrals have an earthiness, an of-the-earthiness which is perhaps lost in the dazzle of the spectacular York Minster.

I pay my museum entry, which includes a 10% discount for the café which is closed for refurbishment, and continue my tour, this time in an anticlockwise direction. I stop at the astronomical clock at the far end of the south transept and watch from the sidelines as a vicar of unknown standing in the Church of England hierarchy intones a midday prayer. She is praying for the parliamentarians debating the Assisted Dying Bill today.

Before I really have the chance to come to terms with it, I am in the choir at the entrance to the feretory containing the earthly remains of St Cuthbert. I don’t rush in. There is a list of all the previous bishops on a board to consult first. One notable name is Thomas Wolsey, of Wolf Hall prominence, of which I’ve lately been enjoying the new series.

The south window opposite the feretory is a modern piece depicting the life and cult of St Cuthbert as well as paying tribute to the coal miners of Durham.

Inside the feretory, there is a pleasing lack of interpretation. It is an intimate space in unusual contrast to the vastness of its wider housing. Cuthbert lies below a great stone slab, simply inscribed with the word Cvthbertvs. I briefly stand over him and then take a seat on one of the surrounding wooden benches.

A strange series of events has brought me here. Immediately, the fantastic novel by Benjamin Myres, Cuddy. It begins with the saint’s death, moving to the monks who carried his casket the length and breadth of Northumbria for over a century, to the building of the cathedral, the imprisonment of the Covenanters, his disinterment in the 19th century to the present day.

Before the novel, Cuddy I walked the St Cuthbert’s Way which starts at Melrose Abbey and crosses the Scottish-English border from West to East, ending at Lindisfarne.

Ultimately, though, my relationship with Cuthbert began through my friend Charles Wright whom I met in student halls and stayed good friends with to graduation and beyond. In the early summer just before graduation Charles and his friend John embarked on the St Cuthbert’s Way. Always that bit more adventurous than me, he was camping along the route and eschewed hostels. I remember him telling me about the saint’s heroic feats of endurance. St Cuthbert would immerse himself in the ice-cold waters of the North Sea and pray for hours on end. He always sought greater isolation and more extreme tests of faith. Even windswept Lindisfarne was too tainted by worldly comforts for Cuthbert. He relocated to Inner Farne – an island off an island – to find the austerity he craved.

Charles passed away suddenly from a dormant heart condition on 7 April 2020. The national lockdown had been announced two weeks earlier.

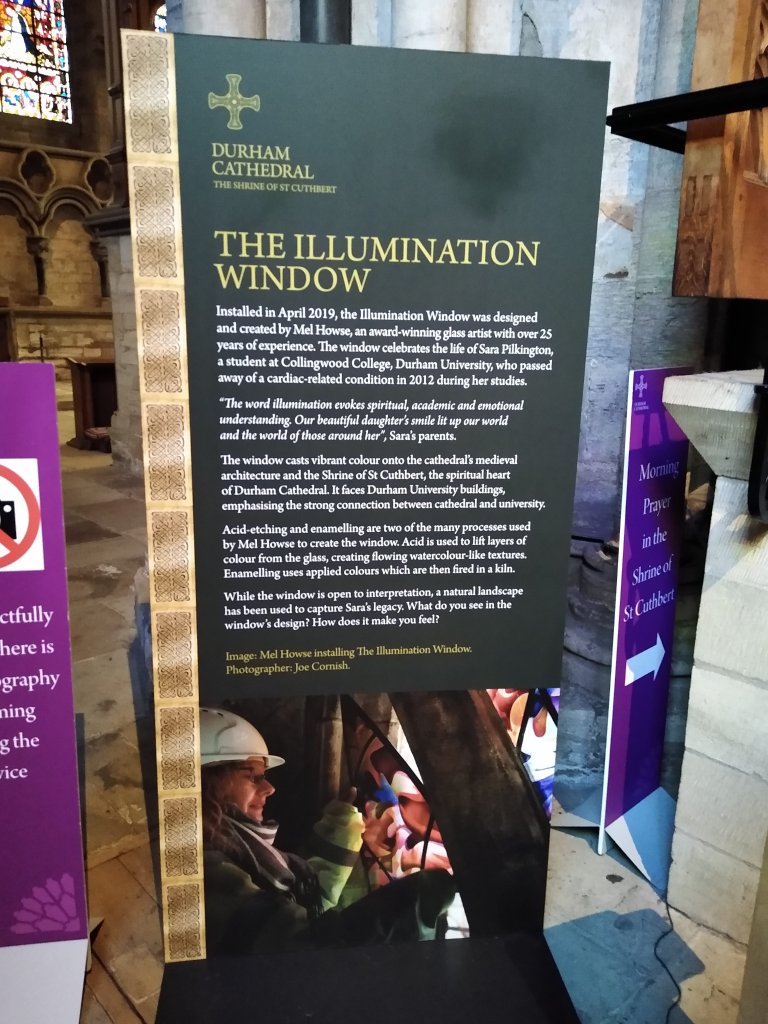

Exiting the feretory, there is an entire window on the north side of the cathedral, finished in 2019, dedicated to Sara Pilkington, an art student who died from a cardiac condition in her final year of studies.